As a child, a cold rainy day in New England meant leafing through my nature books, especially the National Geographic Society’s Wild Animals of North America. It was the illustration of the musk ox that most often captured my 8-year-old imagination. The magnificent bull pictured seemed to belong in the Pleistocene epoch, alongside woolly mammoths, woolly rhinos and Smilodon. Yet the musk ox amazingly still exists in today’s Arctic world.

Sixty years and 40 children’s books later, I was reminded of this youthful fascination when my daughter moved to Alaska. She spoke excitedly about the Musk Ox Farm, a historic farm just outside of Palmer where 80 animals roamed, all well cared for and gently combed for their extremely warm qiviut fiber. It is curious how certain childhood memories are indelible. I instantly pictured that mysterious illustration from my book and started planning a visit.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/52/0952a07d-0e3a-4ff9-b1c8-a39a8030fb59/janbrettmuskoxfarmpalmerak.jpg)

The short trip from Anchorage to Eagle River and on to Palmer set the stage. The Eagle River is at one end of the famous Crow Pass trail, and bald eagles soared above us. We were lucky that the weather was clear, and we had a magnificent view of Denali and its neighboring peaks from the Carrs grocery store parking lot in Eagle River. On to the Knik River Crossing, with its cautionary sign displaying the number of moose-vehicle collisions that year. Ahead was the turnout for the Knik Glacier, one of the few named glaciers accessible by a highway. The whimsical carved patterns and colors formed in the ice at the terminus hint at the relentless force of nature. When we arrived in the Matanuska Valley, framed by the beautiful Chugach Mountains, the view was majestic. The red buildings of the farm gave way to miles of snow-covered pasture dotted with romping musk oxen.

Being fascinated by musk oxen and plotting a picture book about them meant many visits to the Musk Ox Farm. When I was choosing animals to shelter under my musk ox character Cozy during a storm in the original Cozy story a few years ago, I wanted to add a rollicking, lovable creature that would mix things up a bit. Wait! Isn’t that a good description of an Alaskan sled dog? So off we went to mush some Iditarod winners at Dallas Seavey’s kennel in Talkeetna. The experience made my illustrations more authentic, but also more challenging. Capturing all that joyous, mischievous energy was like putting lightning in a bottle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c6/11/c6113111-af0c-4dbf-a441-f8ec545110ac/gettyimages-109487253.jpg)

When I’m painting an Alaskan creature, I love seeing it in the wild; it is inspiring and instructional. But I need details, so I went to the University of Alaska Museum of the North in Fairbanks to see mounted specimens of an arctic fox, a snowy owl and a wolverine. I took artistic license with the wolverine. As the wolverine is an animal that is feared and sometimes disliked, I wanted to give it a sympathetic plight. In Cozy, it fell into freezing water and was covered in ice balls. This was fun to illustrate, but I had read that the wolverine’s glossy coat actually ensures snow and ice do not stick to it. So I knowingly made an exception and allowed the story to rule in this case.

After one trip to the Musk Ox Farm, Mark Austin, the nonprofit’s director, came running after me as I was leaving the parking lot. “Remember,” he called, “you can’t see their small tails under their coats!” I knew that, I thought smugly. Then he added, “And the pupils are horizontal like a goat’s.” Whoops! I could have made an embarrassing mistake. It made me recall my visit to the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago years ago, to see a polar bear up close during an anesthetized medical exam. His tongue was gray (polar bears have black skin), not pink as I had in my original illustrations for The Three Snow Bears, my 2007 twist on Goldilocks and the Three Bears. I was relieved twice over, first because I had time to change the color before the book went to print, and secondly because I didn’t have to find out the hard way.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/87/70/8770b805-8f71-4e3e-b9fa-df3618667a66/unknown-10.jpeg)

The original Cozy tells the story of Cozy the musk ox being left by himself in a big storm. One by one, a snowshoe hare, snowy owl, arctic fox and others take shelter under his warm tent-like coat. When I first saw the musk ox herd roaming around the valley, their silky wool coats swung like skirts, and I had to see what was hidden underneath. What I found after meeting an older tame animal named Littleman were stocky white legs and what seemed like a warm little house. I had the beginnings of my story.

Musk oxen still held me under their spell when on another visit to the Matanuska Valley I watched a lovely female coyly prancing very close to the bull’s pasture. The bulls were snorting, I heard a bellow or two, and there was much head bashing (their way of showing who is strongest). They were so animated that all I could think of was, with all this romance in the air, what if Cozy wasn’t the strongest? Would he still be able to impress his lady love? A new book idea set me off on new Alaskan adventures.

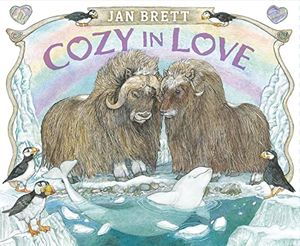

Cozy in Love

This lovable companion to Jan Brett's instant New York Times bestselling winter classic, Cozy, shows that kindness and cleverness can capture a heart.

The next trip was by helicopter to the Sheldon Chalet on Denali. In the 1930s, Bradford Washburn, explorer, mountaineer and cartographer, and Don Sheldon, bush pilot extraordinaire, built a hut on a nunatak sticking up from the Ruth Glacier ten miles from the summit that they used as the base to map Denali, North America’s tallest mountain. Recently, Sheldon’s adult children built a window into this seldom seen world, a five-room hotel a short hike from the existing original hut. My family often visited the Boston Museum of Science, where Bradford Washburn was the director for 41 years (1939-1980), and I remember seeing the room-sized replica of Denali, then called Mount McKinley, showing the Ruth Glacier.

I had hoped to see the aurora borealis to paint in my illustrations, but instead we were treated to alpenglow, the rosy glow from hourslong spellbinding sunrises and sunsets. The vistas inspired the settings for Cozy in Love. Arctic animals tend to be white, gray and brown, so I relied on the sky for its ethereal colors. In Cozy in Love, Cozy wins the affection of his lady love not in the usual way of the males bashing heads during rutting season to see who is dominant, but by demonstrating his big heart and science knowledge. He saves his beluga whale friend trapped by ice by pushing glacier rocks into the small inlet to bring up the water level and free her.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/13/e913f9c7-b9bd-4366-9e29-2be516973a27/unknown-9.jpeg)

Then we set off to stay at Kenai Fjords Wilderness Lodge, a log cabin hotel on Fox Island near Resurrection Bay, a two-hour boat ride from Seward. Walking on a beach made up of heart-shaped stones, I was enchanted by the horned puffins flying like aerial ballerinas behind a waterfall. After a closer look at their large yellow and orange beaks and clownlike faces, I knew they were the perfect cupids for the Cozy in Love story. I made a stop at the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward to see the birds up close. I was able to see their gait, how they swam on the water and dove under it like penguins, and the texture of their feathers and feet. I was also thrilled to see colorful sea stars and shore-life exhibits, which added details to the illustrations in my borders. With my border illustrations, I can move my story along, introduce side plots, establish a sense of place, add humor or create a surprise for later in the story by including some actions of which the main characters are not aware.

A nature cruise out of Seward to a calving glacier sparked my imagination further. As we boarded, sea lions played about. While leaving the harbor, we saw sea otters, humpback whales and then one of the world’s most beautiful ducks, the harlequin. Out on the bay, we saw orcas attracted by spheres of schooling fish. In the fjord nearing the glacier, a black bear swam across our vessel’s path. At the glacier’s terminus, harbor seals floated on the jagged, small pieces of ice calved from the headwall. On the nearby rock face, mountain goats posed with their adorable kids. (Although I must add here that the most adorable babies I saw on the whole trip to Alaska were the musk oxen calves.) On the return trip we passed many murre and crested puffin rookeries and groups of Dall’s porpoises.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6a/74/6a74705e-b92b-4a64-b0fc-26658fb2d400/gettyimages-1342094566.jpg)

Next we drove north through the Kenai Peninsula to Anchorage. Turnagain Arm, south of Anchorage, is an extensive, 45-mile tidal inlet where there is a tidal bore. If the tide is right, people even surf on the wave of water! It was discovered by James Cook in 1778 and is a known place for spotting beluga whales and mountain goats on the nearby rocky cliffs. Here, the last gift of abundant wildlife appeared. A new and beautiful animal character joined my story when we sighted a pod of beluga whales. White, lacking a dorsal fin like their narwhal cousins, they are called canaries of the sea for their chirps and musical vocalizations heard through the hulls of ships. I thought, “thank you, Alaska,” for this last introduction to one of the North’s fabled creatures.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cc/69/cc69087c-3fce-48a8-9c48-dff4dc82e568/gettyimages-566438909.jpg)

As a final postscript: We visited Juneau in June and helicoptered up to the Mendenhall Glacier. Glaciers are formidable, otherworldly, strangely moving things. As I stood on the mile-thick ice watching the dog teams in summer practice, a blue-green hole caught my eye. It was not a crevasse but a moulin, a drain hole plumbing the depths of the icy world. My imagination soared again. Could it be a rabbit hole? A rabbit with a waistcoat and pocket watch? Perhaps many fascinating Alaskan creatures, ones that couldn't fit in Cozy or Cozy in Love, could live down there in a new book? In a secret world under the ice… an Alice in Wonderland of Alaska! Back home in Massachusetts, my memories gathered, creating a snowy, icy, furry, feathery muse to guide me toward the next book.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1061x707:1062x708)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/32/2f320007-f22c-41a3-a3e3-1b4b97c97531/gettyimages-1145029273.jpg)