In June 2017, with a photo of the Museo De Las Américas in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Wally Koval and his wife, Amanda, launched Accidentally Wes Anderson, a travel-based Instagram account that would soon become a sensation. The photos—there are now more than 1,200 of them from spots around the world—embody the basics of filmmaker Wes Anderson’s aesthetic: a colorful palette, symmetrical features, a feeling of nostalgia, a fascinating story. The account has bloomed to more than a million followers, a community of fans who love Wes Anderson’s style from movies like The Royal Tenenbaums, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Rushmore, and more. The community submits more than 3,000 photos a month from their own travels in hopes that they will appear on the account.

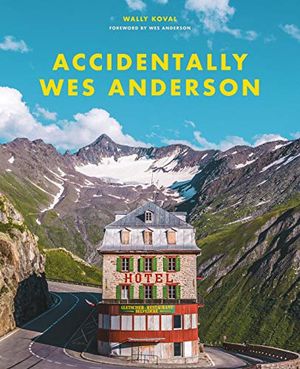

Koval’s Instagram account has now been turned into a book, Accidentally Wes Anderson, with a series of more than 200 photos of places that embody the spirit of both Anderson and the online collection. Anderson himself wrote the foreword to the book, noting, “I now understand what it means to be accidentally myself. Thank you. I am still confused what it means to be deliberately me, if that is even what I am, but that is not important.”

What is important—to the book and the community, at least—is that the photos capture a specific feel. The beauty of a Wes Anderson-esque location isn’t just from the colors, design and style. It’s also from a unique story, something about that particular spot that adds a bit of quirkiness and metaphorical color.

Accidentally Wes Anderson

A visual adventure of Wes Anderson proportions, authorized by the legendary filmmaker himself: stunning photographs of real-life places that seem plucked from the just-so world of his films, presented with fascinating human stories behind each façade.

“A lot of these places, someone would say, ‘Oh, it’s just a bank,’” Koval says. “And you’re like, 'No. Guess what? Gather round, because I’m going to blow your mind.'”

These are ten of our favorite spots from Accidentally Wes Anderson, and the incredible stories behind them.

Central Fire Station; Marfa, Texas

Marfa’s fire station has had some connection to water since the town was first built in 1883. At that time, Marfa was a water stop for steam engines that needed refilling on the route between El Paso and San Antonio. In 1938, the pink firehouse was built to house the fire department established in the early 1900s. Now, 17 volunteer firefighters occupy the space.

“This one is a perfect pink firehouse, so that’s a good starting point,” Koval says about what makes it accidentally Wes Anderson. But what you wouldn’t know from just looking at the fire station is that those 17 volunteers who typically watch over a population of 1,700 people—a small enough amount that the entire town could fit into a single subway train in New York, Koval says—take on much more responsibility for three weeks every fall. During the annual Marfa Open Art Festival, more than 40,000 people from all over the world descend on the town to view visual arts of all kinds, leaving the firefighters (who mostly operate on donations) to handle the overflow.

Roberts Cottages; Oceanside, California

In 1928, developer A.J. Clark built 24 pink beach cottages, situated in two rows right on the beach, in hopes that Oceanside's marketing would pull in visitors to rent out the homes. The city had a unique tactic for gathering tourists. Officials had obtained a quote from a doctor and published it in an 1888 tourism booklet: “The invalid finds health and bright spirits, the pleasure seeker finds variety and amusement.” It worked, and people flocked to the town. Now, the cottages are individually owned rental homes managed by Pacific Coast Real Estate.

“If I put out five quotes and asked which quote is associated with this place, you would probably pick all four others before you picked that one,” Koval says. The cottages themselves have a Wes Anderson aesthetic to them, but that story really seals the deal. “It’s this intersection of distinctive design and aesthetic with this unexpected narrative, and when you find that, that is where the connection comes.”

Post Office; Wrangell, Alaska

The mural on the walls of this 1937 New Deal-era post office traveled 3,500 miles by train to be installed. New-York-based artists Marianne Greer Appel (who later became a Muppets designer) and her husband, Austin “Meck” Mecklem, painted the piece as a commission of the federal Treasury Section of Fine Arts. The couple bid on a proposal to paint a mural for the post office and won. “Old Town in Alaska” shows Wrangell’s harbor and the beauty of the Alaskan coast; when it was finished in 1943, the couple shipped it off on the train. It took two months for transport and installation—and that piece of art is one of the things keeping the post office in business.

“Three thousand people live [in Wrangell],” Koval says. “They don’t have a postman. The community was offered standard mail delivery, and they unanimously voted against it because they all like going to the post office to pick up their mail.”

Hotel Opera; Prague, Czech Republic

The bright pink 1890 Hotel Opera in Prague’s New Town was one of the first images Koval dubbed Accidentally Wes Anderson for Instagram—and one of the first choices for the book itself. It has a perfect trio of Wes Anderson qualities: the design, a unique story, and the quirkiness of not actually being located close to the State Opera building. The Hotel Opera was meant to be a family-run business, owned by local Karel Češka. But the communist regime in World War II commandeered the building, and instead of using it, left it vacant for more than 40 years. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, the hotel was given back to the Češka family, who then spent years renovating it and returning it to its former glory. Hotel Opera is still in operation today.

Cable Car; Cologne, Germany

In 1957, Cologne installed the Cologne Cable Car, a gondola lift taking passengers on a 15-minute, half-mile ride over the Rhine. Originally, it was constructed for the Bundesgartenschau, a horticultural festival that still happens biennially; from the gondola, you can see the entire city, including any garden installations below.

Drama reached the bright gondola cars in 2017, when one of them crashed into a support pillar, leaving passengers stranded along the line for hours as the city worked to bring them down using a winch system. (There were no injuries, and the cable car has since returned to normal operations.) The beautiful photo, combined with this random human experience, turns this photo into an Accidentally Wes Anderson shot, Koval says.

“Two people, Martina and Hans-Peter Rieger, were rescued first,” he says. “They were celebrating their 41st wedding anniversary and told reporters they’d never forget their day out in Cologne.”

Ascensor da Bica; Lisbon, Portugal

This photo, Koval says, was another that he knew would be in the book from the get-go. “It just fits,” he says. “It’s beautiful.” The funicular, built in 1892, takes passengers up one of the steepest hills in Lisbon. Though it’s now electrified, it started as a water-powered tram. When a car reached the top of the hill, it was filled with water. The weight of the water carried that car back down the hill, pulling up a twin car, which had emptied its own water at the bottom. In 1896, four years after it opened, the tram was converted to steam power, and then fully electrified in 1924.

Amer Fort; Rajasthan, India

Built in 1592, this four-level sandstone and marble fort and palace is full of tiny details that make it a real work of art. It had an ancient air conditioning system, where cool air flowed over perfumed water and then through channels under rooms to keep the heat out and a pleasant smell in. Mosaics are everywhere throughout the structure, including an interactive marble one showing two butterflies and a flower; the flower spins to reveal seven different images. Koval’s favorite feature of Amer Fort, though, is called the Mirror Palace. One of the kings in the fort, King Man Singh, built it in the 16th century for his queen, who loved to sleep outside under the stars. Ancient custom didn’t allow women to sleep outside, though, so the king hired architects to replicate the experience indoors. They created intricate mosaic detailing out of glass, so when just two candles are lit in the room at night, the entire room sparkles like the night sky.

The White Cyclone at Nagashima Spa Land; Kuwana, Japan

If you ask Koval, the White Cyclone roller coaster has a mystical quality to it. “You look at the photo, and it looks like it doesn't exist here,” he says. “It looks fake. It looks like it’s from a dream sequence.” The coaster, erected in 1994 with enough wood to build a thousand homes, was one of Japan’s biggest wooden roller coasters, but it no longer exists. Japan has very strict tree felling laws, which makes wooden coasters extremely rare. So in 2018, acknowledging that the White Cyclone deteriorated some in its 14-year-run, the park, instead of fixing it with more wood, tore it down and replaced it with a ride made from steel.

Wharf Shed; Glenorchy, New Zealand

Glenorchy’s wharf shed, built in 1885, was once the only access point to the town on New Zealand's South Island, with all visitors and residents arriving by steamboat since the town had no road connecting it to anything nearby. By the 1950s, the wharf shed fell out of use—it had become so wobbly that people compared it to walking the plank—and the 250 residents of Glenorchy became even more isolated. So the townspeople joined together in an effort to get a 28-mile road built from Glenorchy to Queenstown, with the push led by locals Reta Groves and Tommy Thomson. The couple had three growing children, and proper medical care was a steamer ride away. Driven by concern for their children, Tommy gathered the townspeople and began to bulldoze a road.

“He went out, got this tractor, and started bulldozing,” Koval says. “Then he would sleep and then bulldoze more and then sleep and bulldoze some more, and then, finally, there was a road to Glenorchy.”

The wharf shed washed away a few times, but it was always rebuilt by the townspeople. The Glenorchy sign that once faced the water now faces into the town, and the building itself holds the historical society and a small museum.

Crawley Edge Boatshed; Perth, WA, Australia

“There is nothing spectacular about this,” Koval says of the Crawley Edge boatshed. It doesn’t have a fascinating origin story. It’s a family-owned boatshed at the end of a pier jutting out into the Swan River. That’s it. But somehow, it morphed into the most popular photo setting in all of Perth. The Nattress family, who owns the boatshed, noticed tourists gradually coming to the structure in the early 2000s. What started out as a few visitors grew and grew to a completely overwhelming number of people. The amount of tourists snapping selfies at the spot grew so large that in 2019, the city built a $400,000 solar-powered toilet facility there. Interest in the boatshed can be partially attributed to photo spread on social media, but no one really knows why this unremarkable blue shed became so popular. The site's even been the subject of doctoral studies, and yet there’s still no solid explanation.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/33/9f33fc01-7ade-4b7f-983a-485b6f319675/accidentally_wes_anderson_mobile_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/da/79da6fc3-0518-4541-8007-2961cb0a55c9/accidentally_wes_anderson_social_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)