The forest trail I was hiking into the Kiso Mountains of Japan had the dreamlike beauty of an anime fantasy. Curtains of gentle rain, the tail-end of a typhoon in the South China Sea, were drifting across worn cobblestones that had been laid four centuries ago, swelling the river rushing below and waterfalls that burbled in dense bamboo groves. And yet, every hundred yards or so, a brass bell was hung with an alarming sign: “Ring Hard Against Bears.” Only a few hours earlier, I had been in Tokyo among futuristic skyscrapers bathed in pulsing neon. Now I had to worry about encounters with carnivorous beasts? It seemed wildly unlikely, but, then again, travelers have for centuries stayed on their toes in this fairytale landscape. A Japanese guidebook I was carrying, written in 1810, included dire warnings about supernatural threats: Solitary wayfarers met on remote trails might really be ghosts, or magical animals in human form. Beautiful women walking alone were particularly dangerous, it was thought, as they could be white foxes who would lure the unwary into disaster.

Modern Japan seemed even more distant when I emerged from the woods into the hamlet of Otsumago. Not a soul could be seen in the only laneway. The carved wooden balconies of antique houses leaned protectively above, each one garlanded with chrysanthemums, persimmons and mandarin trees, and adorned with glowing lanterns. I identified my lodgings, the Maruya Inn, from a lacquered sign. It had first opened its doors in 1789, the year Europe was plunging into the French Revolution, harbinger of decades of chaos in the West. At the same time here in rural Japan—feudal, hermetic, entirely unique—an era of peace and prosperity was underway in a society as intricate as a mechanical clock, and this remote mountain hostelry was welcoming a daily parade of traveling samurai, scholars, poets and sightseers.

There was no answer when I called in the door, so, taking off my shoes, I followed a corridor of lacquered wood to an open hearth, where a blackened iron kettle hung. At the top of creaking stairs were three simple guest rooms, each with springy woven mats underfoot, sliding paper-screen doors and futons. My 1810 guidebook offered travelers advice on settling in to lodging: After checking in, the author suggests, locate the bathroom, secure your bedroom door, then identify the exits in case of fire.

The only sign of the 21st century was the vending machine by the front doorway, its soft electric glow silhouetting cans of iced coffee, luridly colored fruit sodas and origami kits. And the antique aura was hardly broken when the owners, a young couple with a toddler and a puppy, emerged with a pot of green tea. Their elderly parents were the inn’s cooks, and soon we all gathered for a traditional country dinner of lake fish and wild mushrooms over soba (buckwheat noodles). Looking out through the shutters later that night, I saw the clouds part briefly to reveal a cascade of brilliant stars. It was the same timeless view seen by one of Japan’s many travel-loving poets, Kobayashi Issa (1763-1828), who had also hiked this route, known as the Nakasendo Road, and was inspired to compose a haiku:

Flowing right in

to the Kiso Mountains:

the Milky Way.

From 1600 to 1868, a secretive period under the Tokugawa dynasty of shoguns, or military overlords, Japan would largely cut itself off from the rest of the world. Foreign traders were isolated like plague-bearers; by law, a few uncouth, louse-ridden Dutch “barbarians” and Jesuits were permitted in the port of Nagasaki, but none was allowed beyond the town walls. Any Japanese who tried to leave was executed. A rich aura of mystery has hung over the era, with distorted visions filtering to the outside world that have endured until recently. “There used to be an image of Japan as an entirely rigid country, with the people locked in poverty under an oppressive military system,” says Andrew Gordon of Harvard University, author of A Modern History of Japan: from Tokugawa Times to the Present. But the 270-year-long time capsule is now regarded as more fluid and rich, he says. “A lot of the harshest feudal laws were not enforced. It was very lively socially and culturally, with a great deal of freedom and movement within the system.”

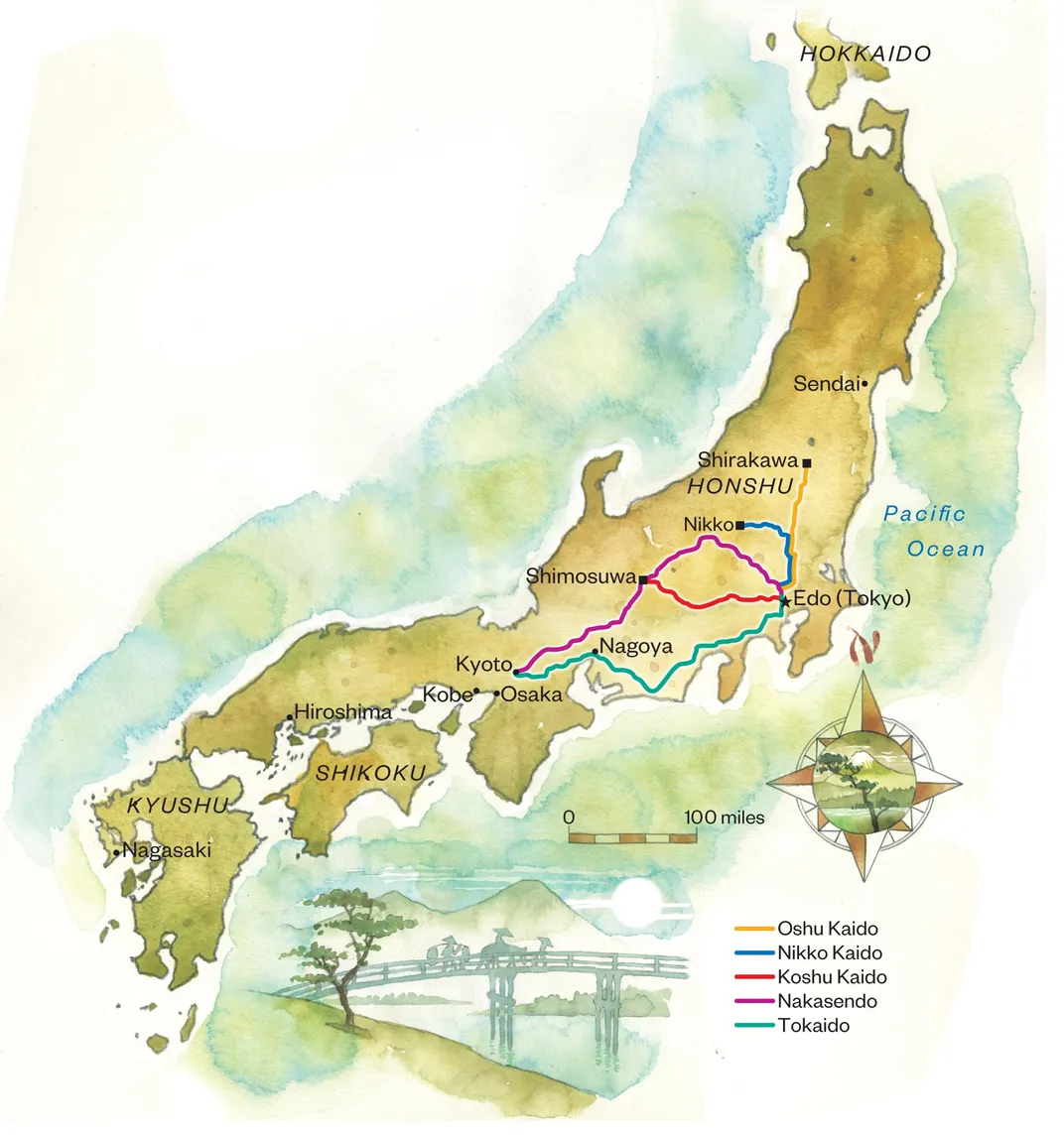

It was the Eastern version of the Pax Romana. The new era had begun dramatically in 1600, when centuries of civil wars between Japan’s 250-odd warlords came to an end with a cataclysmic battle on the mist-shrouded plains of Sekigahara. The visionary, icily cool general Tokugawa Ieyasu—a man described in James Clavell’s fictionalized account Shogun as being “as clever as a Machiavelli and as ruthless as Attila the Hun”—formally became shogun in 1603 and moved the seat of government from Kyoto, where the emperor resided as a figurehead, to Edo (now Toyko), thus giving the era its most common name, “the Edo period.” (Tokugawa is about to receive a renewed burst of fame next year on FX with a new adaptation of Clavell’s novel.) He immediately set about wiping out all bandits from the countryside and building a new communication system for his domain. From a bridge in front of his palace in Edo, the five highways (called the Tokaido, Nakasendo, Nikko Kaido, Oshu Kaido and Koshu Kaido) spread in a web across crescent-shaped Honshu, largest of Japan’s four main islands.

Expanding in many areas on ancient foot trails, the arteries were first constructed to secure Tokugawa’s power, allowing easy transit for officials and a way to monitor the populace. Although beautifully engineered and referred to as “highways,” the tree-lined paths, which were mostly of stone, were all designed for foot traffic, since wheeled transport was banned and only top-ranking samurai, the elite warrior class, were legally permitted to travel on horseback. An elaborate infrastructure was created along the routes, with carved road markers placed every ri, 2.44 miles, and 248 “post stations” constructed every five or six miles, each with a luxurious inn and a relay center for fresh porters. Travelers were forbidden to stray from the set routes and were issued wooden passports that would be examined at regular security checkpoints, kneeling in the sand before local magistrates while their luggage was searched for firearms.

Among the first beneficiaries of the highway system were the daimyo, feudal lords, who were required by the shogun to spend every second year with their entourages in Edo, creating regular spasms of traffic around the provinces. But the side effect was to usher in one of history’s golden ages of tourism. “The shoguns were not trying to promote leisure travel,” says Laura Nenzi, professor of history at the University of Tennessee and author of Excursions in Identity: Travel and the Intersection of Place, Gender, and Status in Edo Japan. “But as a means of social control, the highway system backfired. It was so efficient that everyone could take advantage of it. By the late 1700s, Japan had a whole travel industry in place.” Japan was by then teeming with 30 million people, many of them highly cultured—the era also consolidated such quintessential arts as kabuki theater, jujutsu, haiku poetry and bonsai trees—and taking advantage of the economic good times, it became fashionable to hit the road. “Now is the time to visit all the celebrated places in the country,” the author Jippensha Ikku declared in 1802, “and fill our heads with what we have seen, so that when we become old and bald we will have something to talk about over the teacups.” Like the sophisticated British aristocrats on grand tours of Europe, these Japanese sightseers traveled first as a form of education, seeking out renowned historical sites, beloved shrines and scenery. They visited volcanic hot baths for their health. And they went on culinary tours, savoring specialties like yuba, tofu skin prepared by monks a dozen different ways in Nikko. “Every strata of society was on the road,” explains the scholar William Scott Wilson, who translated much of the poetry from the period now available in English. “Samurai, priests, prostitutes, kids out for a lark, and people who just wanted to get the hell out of town.”

The coastal highway from Kyoto to Edo, known as the Tokaido, could be comfortably traveled in 15 days and saw a constant stream of traffic. And on all five highways, the infrastructure expanded to cater to the travel craze, with the post stations attracting armies of souvenir vendors, fast-food cooks and professional guides, and sprouting inns that catered to every budget. While most were decent, some of the one-star lodgings were noisy and squalid, as described by one haiku:

Fleas and lice,

the horse pissing

next to my pillow.

Japan’s thriving publishing industry catered to the trend with the likes of my 1810 volume, Ryoko Yojinshu, roughly, Travel Tips (and published in a translation by Wilson as Afoot in Japan). Written by a little-known figure named Yasumi Roan, the guide offers 61 pieces of advice, plus “Instructional Poems” for beginners on the Japanese road, covering everything from etiquette to how to treat sore feet.

There were best-selling collections of haikus by celebrated poets who caught the travel bug, pioneered by Matsuo Basho (1644-94), who was wont to disappear for months at a time “roughing it,” begging and scribbling as he went. His shoestring classics include Travelogue of Weather-Beaten Bones and The Knapsack Notebook, both titles that Jack Kerouac might have chosen. Even famous artists hit the road, capturing postcard-like scenes of daily life at every stop—travelers enjoying hot baths, or being ferried across rivers by near-naked oarsmen—then binding them into souvenir volumes of polychrome woodblock prints with tourist-friendly titles like The Sixty Nine Stations of the Kisokaido Road or One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. Many later filtered to Europe and the United States. The works of the master Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) were so highly regarded that they were copied by the young Vincent van Gogh and collected by Frank Lloyd Wright. For travelers, following the remains of the shogun age provides a tantalizing doorway into a world rarely seen by outsiders. The five ancient highways still exist. Like the pagan roads of Europe, most have been paved over, but a few isolated sections have survived, weaving through remote rural landscapes that have remained unchanged for centuries. They promise an immersion into a distant era that remains laden with romance—and a surprising key to understanding modern Japan.

* * *

My journey began as it did centuries ago, in Tokyo, a famously overwhelming megalopolis of 24-hour light and surging crowds. I felt as disoriented as a shipwrecked 18th-century European sailor as I rode speeding subways through the alien cityscape. “Japan is still very isolated from the rest of the world,” noted Pico Iyer, a resident for over 30 years and the author, most recently, of A Beginner’s Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations, adding that it ranks 29th out of 30 countries in Asia for proficiency in English, below North Korea, Indonesia and Cambodia. “To me, it still seems more like another planet.” It was some comfort to recall that travelers have often felt lost in Edo, which by the 18th century was the world’s largest city, packed with theaters, markets and teeming red-light districts.

Luckily, the Japanese have a passion for history, with their television full of splendid period dramas and anime depictions of ancient stories, complete with passionate love affairs, betrayals, murder plots and seppuku, ritual suicides. To facilitate my own transition to the past, I checked into the Hoshinoya Hotel, a 17-story skyscraper sheathed in leaf-shaped latticework, creating a contemporary update of a traditional inn in the heart of the city. The automatic entrance doors were crafted from raw, knotted wood, and opened onto a lobby of polished cedar. Staff swapped my street shoes for cool slippers and secured them in bamboo lockers, then suggested I change into a kimono. The rooms were decorated with the classic mat floors, futons and paper screens to diffuse the city’s neon glow, and there was even a communal, open-air bathhouse on the skyscraper’s rooftop that uses thermal waters pumped from deep under Tokyo.

Stepping outside the doors, I navigated the ancient capital with an app called Oedo Konjaku Monogatari, “Tales From Edo Times Past.” It takes the street map of wherever the user is standing in Tokyo and shows how it looked in the 1800s, 1700s, then 1600s. Clutching my iPhone, I wove past the moat-lined Imperial Palace to the official starting point of the five Tokugawa-era highways, the Nihonbashi, “Japan Bridge.” First built in 1603, it was a favorite subject for artists, who loved the colorful throngs of travelers, merchants and fishmongers. The elegant wooden span was replaced in 1911 by a stolid granite bridge, and is now overshadowed by a very unpicturesque concrete expressway, although its “zero milestone” plaque is still used for all road measurements in Japan. To reimagine the original travel experience, I dashed to the cavernous Edo-Tokyo Museum, where the northern half of the original bridge has been recreated in 1:1 scale. Standing on the polished wooden crest, jostled by Japanese schoolkids, I recalled my guidebook’s 210-year-old advice: “On the first day of a journey, step out firmly but calmly, making sure that your footwear has adapted itself to your feet.” Straw sandals were the norm, so podiatry was a serious matter: The book includes a diagram on how to alleviate foot pain, and suggests a folk remedy, a mash of earthworms and mud, be applied to aching arches.

* * *

Of the five highways, the Nikko Kaido—road to Nikko—had special historical status. The serene mountain aerie 90 miles north of Edo was renowned for its scenery and ornate Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. One of the shrines, Toshogu, is traditionally held to house the remains of the all-conquering shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the dynasty. This balance of nature, history and art was so idyllic that a Japanese saying went, “Never say the word ‘beautiful’ until you have seen Nikko.” Later shoguns would travel there to venerate their ancestors in processions that dwarfed the Elizabethan progresses of Tudor England. Their samurai entourages could number in the thosands, the front of their heads shaven and carrying two swords on their left hip, one long, one short. These parades were a powerful martial spectacle, a river of colorful banners and uniforms, glittering spears and halberds, their numbers clogging up mountain passes for days and providing an economic bonanza for farmers along the route. They were led by heralds who would shout, “Down! Down!,” a warning for commoners to prostrate themselves and avert their eyes, lest samurai test the sharpness of their swords on their necks.

Today, travelers generally reach Nikko on the Tobu train, although it still has its storybook charm. At the station before boarding, I picked up a bento box lunch called “golden treasure,” inspired by an ancient legend of gold buried by a samurai family near the route. It included a tiny shovel to dig up “bullion”—flecks of boiled egg yolk hidden beneath layers of rice and vegetables. In Nikko itself, the shogun’s enomous temple complex still had military echoes: It had been taken over by a kendo tournament, where dozens of black-robed combatants were dueling with bamboo sticks while emitting blood-curdling shrieks. Their gladiatorial cries followed me around Japan’s most lavish shrine, now part of a Unesco World Heritage site, whose every inch has been carved and decorated. The most famous panel, located beneath eaves dripping with gilt, depicts the Three Wise Monkeys, the original of the maxim “See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil.”

As for the ancient highway, there were tantalizing glimpses. A 23-mile stretch to the west of Nikko is lined by 12,000 towering cryptomeria trees, or sugi, that were planted after the death of the first Tokugawa shogun, each nearly 400-year-old elder lovingly numbered and maintained by townsfolk. It’s the longest avenue of trees in the world, but only a short, serene stretch is kept free of cars. Another miraculous survivor is the restored post station of Ouchi-Juku, north of Nikko. Its unpaved main street is lined with whitewashed, thatch-roof strutures, some of which now contain teahouses where soba noodles are eaten with hook-shaped pieces of leek instead of spoons. Its most evocative structure is a honjin (now a museum), one of the luxurious ancient inns built for VIPs: Behind its ornate ceremonial entrance, travelers could luxuriate with private baths, soft bedding and skilled chefs preparing delicacies like steamed eel and fermented octopus in vinegar.

These were vivid connections to the past, but the shogun-era highway itself, I discovered, was gone. To follow one on foot, I would have to travel to more remote locales.

* * *

During the height of the travel boom, from the 1780s to the 1850s, discerning sightseers followed the advice of Confucius: “The man of humanity takes pleasure in the mountains.” And so did I, heading into the spine of Japan to find the last traces of the Nakasendo highway (“central mountain route”). Winding 340 miles from Edo to Kyoto, the trail was long and often rugged, with 69 post stations. Travelers had to brave high passes along trails that would coil in hairpin bends nicknamed dako, “snake crawl,” and cross rickety suspension bridges made of planks tied together by vines. But it was worth every effort for the magical scenery of its core stretch, the Kiso Valley, where 11 post stations were nestled among succulent forests, gorges and soaring peaks—all immortalized by the era’s intrepid poets, who identified, for example, the most sublime spots to watch the rising moon.

Today, travelers can be thankful for the alpine terrain: Bypassed by train lines, two stretches of the Nakasendo Trail were left to quietly decay until the 1960s, when they were salvaged and restored to look much as they did in shogun days. They are hardly a secret but remain relatively little visited, due to the eccentric logistics. And so I set out to hike both sections over three days, hoping to engage with rural Japan in a manner that the haiku master Basho himself once advised: “Do not simply follow in the footsteps of the ancients,” he wrote to his fellow history-lovers; “seek what they sought.”

It took two trains and a bus to get from Tokyo to the former post station of Magome, the southern gateway to the Kiso Valley. Edo-era travelers found it a seedy stopover: Sounding like cranky TripAdvisor reviewers today, one dismissed it as “miserable,” another as “provincial and loutish,” filled with cheap flophouses where the serving girls doubled as prostitutes. In modern Magome, framed by verdant peaks, sleepy streets have a few teahouses and souvenir stores that have been selling the same items for generations: lacquerware boxes, dried fish, mountain herbs and sake from local distilleries. My guidebook advised: “Do not drink too much. / Yet just a little from time to time / is good medicine.” Still, I ordered the ancient energy food for hikers, gohei, rice balls on skewers grilled in sweet chestnut sauce, and then I set off into a forest that was dripping from a summer downpour.

Once again, I had heeded the Ryoko Yojinshu’s advice for beginners: Pack light. (“You may think that you need to bring a lot of things, but in fact, they will only become troublesome.”) In Edo Japan, this did not mean stinting on art: The author’s list of essentials includes ink and brush for drawing and a journal for poems. For the refined sightseers, one of travel’s great pleasures was to compose their own haikus, inspired by the glimpse of a deer or the sight of falling autumn leaves, often in homage to long-dead poets they admired. Over the generations, the layers of literature became a tangible part of the landscape as locals engraved the most beloved verse on trailside rocks.

Some remain today, such as a haiku by Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902):

White clouds,

green leaves, young leaves,

for miles and miles.

A modern sign I passed was almost as poetic: “When it sees trash, the mountain cries.” Wooden plaques identified sites with enigmatic names like The Male Waterfall and The Female Waterfall, or advised that I had reached a “lucky point” in numerology, 777 meters above sea level—“a powerful spot of the happiness.” Another identified a “baby bearing” tree: A newborn was once found there, and women travelers still boil the bark as a fertility tea.

But their impact paled beside the urgent yellow placards warning about bear attacks, accompanied by the brass bells that were placed every hundred yards or so. Far-fetched as it seemed, locals took the threat seriously: A store in Magome had displayed a map covered with red crosses to mark recent bear sightings, and every Japanese hiker I met wore a tinkling “bear bell” on their pack strap. It was some consolation to recall that wild animals were far more of a concern for hikers in the Edo period. My caution-filled guidebook warned that travelers should be on the lookout for wolves, wild pigs and poisonous snakes called mamushi, pit vipers. The author recommends striking the path with a bamboo staff to scare them off, or smearing the soles of your sandals with cow manure.

A half-hour later, a bamboo grove began to part near the trail ahead. I froze, half-expecting to be mauled by angry bears. Instead, a clan of snow monkeys appeared, swinging back and forth on the flexible stalks like trapeze artists. In fact, I soon found, the Japanese wilderness was close to Edenic. The only bugs I encountered were dragonflies and tiny spiders in webs garlanded with dew. The only vipers had been drowned by villagers in glass jars to make snake wine, a type of sake considered a delicacy. More often, the landscape seemed as elegantly arranged as a temple garden, allowing me to channel the nature-loving Edo poets, whose hearts soared at every step. “The Japanese still have the pantheistic belief that nature is filled with gods,” Iyer had told me. “Deities inhabit every stream and tree and blade of grass.”

As the trail zigzagged above the rushing Kiso River, I could finally imagine the ancient “road culture” in all its high theater. A traveler would pass teams of porters clad only in loincloths and groups of pilgrims wearing broad-rimmed straw hats adorned with symbols, sometimes lugging portable shrines on their backs. There were wealthy travelers being carried in palanquins, wooden boxes with pillows, decorations and fine silk curtains. (My guidebook suggests ginger tea for passengers who suffer from motion sickness.) One could meet slow processions of zattou, blind masseurs, and goze, women troubadours who played the samisen, a three-stringed lute, and trilled classical songs. There were monks who banged drums and tossed amulets to bemused passersby; shaven-headed nuns; country doctors in black jackets, lugging medicine boxes filled with potions. Near the post station of Tsumago, travelers would also encounter vendors selling fresh bear liver, a medicinal treat devoured to gain the animal’s strength.

Today, Tsumago is the crown jewel of post stations. During its restoration, electricity lines were buried, TV antennas removed and vending machines hidden. Cars cannot enter its narrow laneways during daylight hours, and its trees have been manicured. Even the mailman wears period dress.

* * *

The shogunate’s time capsule began to crack in 1853 with the arrival of U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry, who cruised into Edo Bay in a battleship and threatened bombardments if Japan did not open its doors to the West. In 1867, progressive samurai forced the last shogun to cede his powers, in theory, to the 122nd emperor, then only 16 years old, beginning a period that would become known as the Meiji Restoration (after “enlightened rule”). Paradoxically, many of the same men who had purportedly “restored” the ancient imperial institution of the Chrysanthemum Throne became the force behind modernizing Japan. The Westernization program that followed was a cataclysmic shift that would change Asian history.

The old highway systems had one last cameo in this operatic drama. In 1868, the newly coronated teen emperor traveled with 3,300 retainers from Kyoto to Edo along the coastal Tokaido road. He became the first emperor in recorded history to see the Pacific Ocean and Mount Fuji, and ordered his courtiers to compose a poem in their honor. But once he arrived, the young ruler made Edo his capital, with a new name he had recently chosen, Tokyo, and threw the country into the industrialization program that sealed the fate of the old road system. Not long after Japan’s first train line opened, in 1872, woodblock art began to have an elegiac air, depicting locomotives as they trundled past peasants in the rice fields. And yet the highways retained a ghostly grip on the country, shaping the routes of railways and freeways for generations to come. When the country’s first “bullet train” opened in 1964, it followed the route of the Tokaido. And in the latest sci-fi twist, the new maglev (magnetic levitation) superfast train will start operations from Tokyo to Osaka in 2045 —largely passing underground, through the central mountains, following a route shadowing the ancient Nakasendo highway.

As for me on the trail, jumping between centuries began to feel only natural. Hidden among the 18th-century facades of Tsumago, I discovered a tiny clothing store run by a puckish villager named Jun Obara, who proudly explained that he only worked with a colorful material inspired by “sashiko,” once used for the uniforms of Edo-era firefighters. (He explained that their coats were reversible—dull on the outside and luridly colored on the inside, so they could go straight from a fire to a festival.) I spent one night at an onsen, an inn attached to natural hot springs, just as foot-sore Edo-travelers did; men and women today bathe separately, although still unashamedly naked, in square cedar tubs, watching the stars through waves of steam. And every meal was a message from the past, including one 15-course dinner that featured centuries-old specialties like otaguri—“boiled horse’s intestine mixed with miso sauce.”

But perhaps the most haunting connection occurred after I took a local train to Yabuhara to reach the second stretch of the trail and climbed to the 3,600-foot-high Torii Pass. At the summit stood a stone Shinto gate framed by chestnut trees. I climbed the worn stone steps to find an overgrown shrine filled with moss-coated sculptures—images of Buddhist deities and elderly sages in flowing robes who had once tended to the site, one wearing a red bib, considered a protection from demons. The shrine exuded ancient mystery. And yet, through a gap in the trees, was a timeless view of Mount Ontake, a sacred peak that Basho had once admired on the same spot:

Soaring above

the skylark:

the mountain peak!

By the time I returned to Tokyo, the layers of tradition and modernity no longer felt at odds; in fact, the most striking thing was the sense of continuity with the ancient world. “Japan changes on the surface so as not to change on a deeper level,” Pico Iyer explained. “When I first moved to the country 30 years ago, I was surprised by how Western everything looked. But now I am more shocked at how ancient it is, how rooted its culture and beliefs still are in the eighth century.” This time, back at the Hoshinoya Hotel, I took the elevator straight to the rooftop baths to watch the night sky, which was framed by sleek walls as paper lanterns swayed in the summer breeze. Even though Tokyo’s electric glow engulfed the stars, the great wanderers of the Edo era might still manage to feel at home in modern Japan, I realized. As Basho wrote in the poetry collection Narrow Road to the Interior, “The moon and sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on...Every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/81/5b8132a6-d181-4372-984d-33aec1f973db/mobile_opener.jpg)

:focal(761x238:762x239)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/09/c8091d3c-d962-4efa-9898-7bf5e545ecc1/longformopener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)