In 1923, a decade before he became Germany’s chancellor, 34-year-old Adolf Hitler slipped into a beer hall in Munich, where he would make his first clumsy, fledgling grasps at power.

A crowd of around 3,000 had gathered at the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall to hear Gustav Ritter von Kahr, the Bavarian state commissioner, give a speech. As they listened, hundreds of members of Hitler’s SA, the paramilitary group known as the Brownshirts, surrounded the venue. Hitler—then the leader of the nascent Nazi Party—paced inside the foyer, waiting for his big moment.

It came at around 8:45 p.m. on November 8. He threw his beer glass to the floor and made a beeline for the stage, flanked by armed guards. Chaos reigned in the hall; to stifle it, Hitler climbed onto a chair and fired a pistol into the air, then scurried to the stage. “National revolution is underway!” he cried. He explained that 600 armed men now guarded the Bürgerbräukeller, and nobody could leave—not alive, anyway—without his permission. The Bavarian government had been deposed, he claimed, and a new government had risen in its place.

“All of this was, of course, a bluff, but he hoped that it would be true soon enough,” writes historian David King in The Trial of Adolf Hitler: The Beer Hall Putsch and the Rise of Nazi Germany. “He was sweating considerably. He looked crazy, drunk or both.”

The coup attempt—now known as the Beer Hall Putsch—would swiftly be quashed. Two days after the Bürgerbräukeller spectacle ended on November 9, Hitler was arrested. That winter, he was tried for high treason.

Onlookers predicted severe repercussions, certain Hitler would be jailed, deported or even executed. If the man himself wasn’t annihilated, surely any lingering political aspirations he harbored would be.

This month marks the 100th anniversary of Hitler’s failed coup. Contemporary historians emphasize how amateurish these early efforts were. Yet they also stress the lessons the future führer gleaned from his failure. If he couldn’t capture Weimar Germany by force, Hitler would convince the people to hand him the reins.

What led to the coup attempt?

By the time of the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler was already accustomed to failure.

Born in 1889, he grew up near Linz, Austria, where he was a poor student and a high school dropout. Hoping to pursue a career as an artist, he applied to Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts, receiving rejections two years in a row, in 1907 and 1908. He moved to Vienna anyway, spending several aimless years living in a homeless shelter (a social project funded by Jewish philanthropists) and trying to sell his art.

In 1913, Hitler moved to Munich, where he was eventually apprehended for failing to register for the draft back home. (Though he returned for a screening, he failed his physical. Officials deemed him “unsuitable for combat and support duty, too weak, incapable of firing weapons.”) Back in Munich, he requested—and was granted—permission to join the Bavarian Army. “After seven years of privations, disappointments and rejections, the 25-year-old loner finally thought he had found a way out of his disoriented, useless existence,” writes Volker Ullrich in Hitler: Ascent: 1889-1939.

History remembers conflicting accounts of Hitler’s military career. He expressed great pride in his service, later writing that receiving the Iron Cross Second Class was the “happiest day of my life” and that the war more broadly was the “most memorable period of my life.” More recent research, however, reveals that he was something of a loner among his fellow soldiers, some of whom shunned him as a “rear area pig,” based far from the front line. They noticed he spent considerable time in solitude, painting or reading political books.

Weeks before World War I’s end, Hitler was temporarily blinded in a mustard gas attack. As he recovered in a hospital, he learned of yet another failure: Germany’s humiliating defeat on the world stage. He was incensed by the armistice, which German officials signed on November 11, 1918, and later by the Treaty of Versailles, which blamed Germany for the war and forced it to pay billions of dollars in reparations, plunging the country into a financial crisis.

Hitler decided he would “save Germany.” Back in Munich, he attended a meeting of the German Workers’ Party, a far-right group founded by Anton Drexler that would eventually become the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, better known as the Nazi Party. At that meeting, Drexler gave Hitler a copy of his pamphlet “My Political Awakening,” which extolled antisemitic, anticapitalist ideas—ideas that Hitler was already partial to.

The party was then quite small, allowing Hitler, who had taken to making speeches at the group’s meetings, to rise quickly within it. On one occasion, he later recalled, “I talked for 30 minutes, and what I always had felt deep down in my heart, without being able to put it to the test, was here proved to be true: I could make a good speech. At the end of the 30 minutes, it was quite clear that all the people in the little hall had been profoundly impressed.”

In 1920, the Nazis publicized their 25-point platform, a haphazard mixture of antisemitism, nationalism and socialism, all tied to a furious rejection of the Treaty of Versailles. Hitler was elected as the party’s leader the following year.

As Germany struggled to pay the reparations it owed, the economy plummeted—and support for the Nazi Party swelled. Hyperinflation devastated the country, with German currency becoming increasingly worthless with every passing hour. Before World War I, 4 marks had been equivalent to one U.S. dollar. In the beginning of 1923, a dollar equaled 17,000 marks. By November of that year, one dollar equaled 2.2 trillion marks.

As historian Adam Bisno wrote for Smithsonian magazine earlier this year, “The greatest impact of the hyperinflation of 1923 may be the hardest to measure: how it turned Germans against each other, breeding the mistrust and animosity that made Nazism seem like such a good idea to so many people.”

That animosity is what led Hitler to a stage at the Bürgerbräukeller, where he would embark on his biggest failure yet.

What happened during the coup?

On that fateful November night, after Hitler fired his pistol and declared a national revolution, he brought Kahr and two other Bavarian officials—Hans Ritter von Seisser, head of the Bavarian police, and Otto von Lossow, a German general—into an adjoining room. He demanded that these men join his cause, promising them positions in his newly formed government. In Hitler’s vision of the future, the trio would support him as he led a march against the government in Berlin. He thought the coup would mirror Benito Mussolini’s rise to power in 1922, when the Italian dictator had led a march on Rome that culminated in his appointment as prime minister.

Kahr didn’t immediately acquiesce to these plans. Hitler returned to the beer hall, where the crowd was growing agitated. He assured them the coup wasn’t about Kahr, who he hoped would join the cause. Instead, he was acting in opposition to the “Berlin Jew government and the November criminals” who signed the armistice in 1918. Somehow, this speech won over the audience. “Hitler, who had seemed insane to most of the audience only a few minutes before, suddenly mastered the situation,” writes Ullrich. “In a short speech … Hitler completely turned the mood in the beer hall.”

Hitler went on to explain that Kahr and the others were wrestling with their decision. “Can I tell them that you stand behind them?” he asked. The crowd cried out in the affirmative.

The Bavarian leaders reappeared on the stage, where Kahr told the crowds that he had decided to join the uprising. Triumphant, Hitler proclaimed that he intended to “fulfill the promise I made myself five years ago to the day as a blind cripple in an army hospital: never to rest or relax until … a Germany of power and greatness, of freedom and majesty, has been resurrected on the ruins of Germany in its pathetic present-day state.”

That night, Hitler exited the beer hall, rushing to help his followers seize a set of military barracks and leaving the Bavarian leaders in the hands of his cronies. When he returned, he was furious to learn that the trio had been allowed to leave after promising to keep their word. Once free, they immediately turned on Hitler and crushed the coup. “The putsch was thus condemned to failure,” writes Ullrich, “since everything depended on getting the triumvirate behind the uprising.”

With no backup plan or clear destination in mind, Hitler’s supporters decided to stage a march through the city. As several thousand Brownshirts took to the streets, they encountered authorities. In the violence that ensued, 4 police officers and 16 Nazis were killed. A devastated Hitler, meanwhile, was whisked off in a getaway car. He spent the next two days hiding in a friend’s attic. On November 11, 1923, he was arrested and charged with high treason.

What consequences did Hitler face?

When Hitler’s trial began in early 1924, onlookers thought the courtroom drama would be the end of the Nazi Party. Instead, over the course of 24 days, Hitler got the opportunity to sell his extremist ideas to a receptive German public.

“Hitler had a chance to redefine himself as this national hero,” King told the Times of Israel in 2018. “The incident caused headlines all over the international press, and Hitler’s name became known thereafter. He could not have bought the kind of publicity he got at the trial even if he wanted to.”

On the first day of the trial, Hitler gave a speech that lasted over three hours. He spoke of his military service, “trying to show he had the character of a soldier, not a traitor,” writes King in his book. He also spoke of his aimless years in Vienna, when he was “forced to earn my own bread.” Per Hitler’s account—though scholars dispute the timeline—this period cemented his worldview. He left the Austrian city an “absolute antisemite.”

Hitler’s final speech during the trial lasted two hours. He blamed Germany’s decline on Jews and Marxists, reiterating that he had been called upon to restore the country to its former glory. The Beer Hall Putsch, he insisted, had not failed. Popular support for his vision was growing.

“You may pronounce us guilty a thousand times,” he told the judge, “but the goddess who presides over the eternal court of history will with a smile tear in pieces the charge of the public prosecutor and the verdict of this court. For she acquits us.”

On April 1, Hitler and several of his co-conspirators were found guilty of high treason. Despite the verdict, his sentence was astonishingly light: five years in prison, which would ultimately be shortened to just nine months.

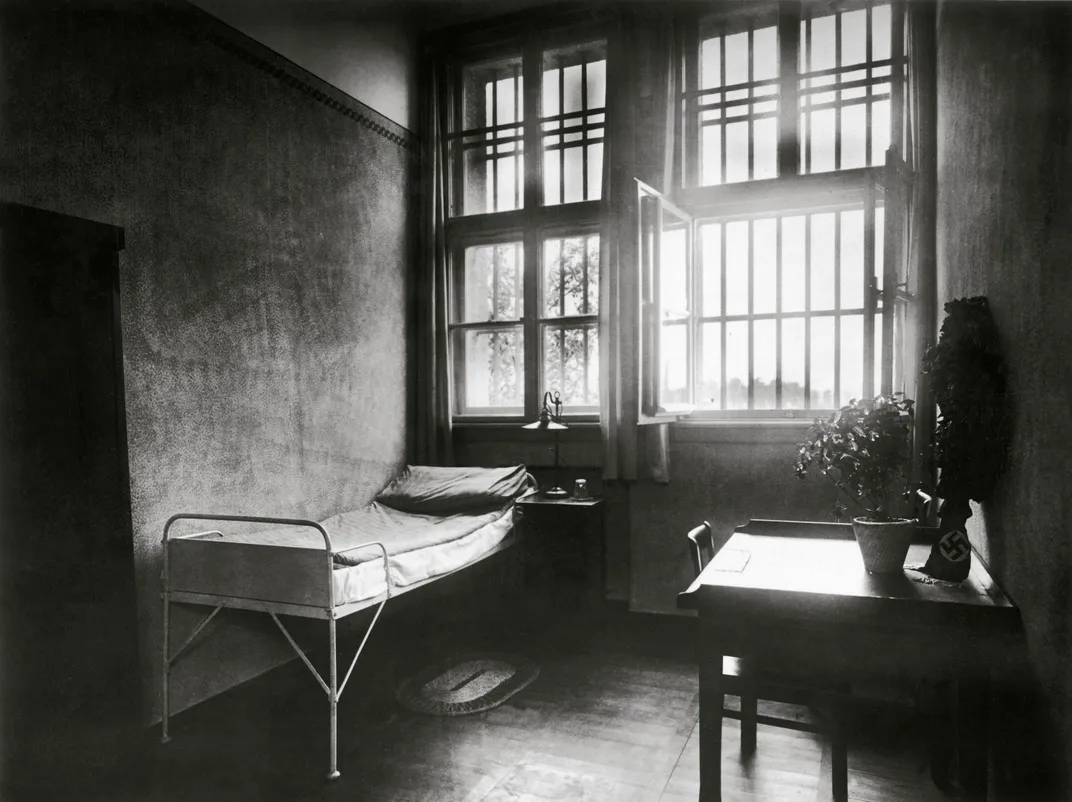

During his imprisonment, as support for Nazism swelled, Hitler wrote the first volume of Mein Kampf, his autobiographical manifesto. The text presented a cohesive (though largely fabricated) narrative of his life and revealed the foundations of his worldview: that Germany’s defeat in World War I had come from within, with the “November criminals” stabbing it in the back. All of this, Hitler believed, was part of a larger conspiracy in which Jews were plotting to take power for themselves.

While historians debate precisely when Hitler’s antisemitic views crystallized, they were certainly strengthened during his stint in prison. As Ullrich writes, in Mein Kampf, “Hitler no longer spoke of deporting or driving out Jews: He now used words like ‘destruction’ and ‘eradication.’”

How did the Beer Hall Putsch herald Hitler’s rise to power?

When Hitler was released from prison in December 1924, he was banned from giving speeches in much of Germany. What’s more, the German economy had started to improve, weakening the Nazi leader’s appeal. Yet both of those limitations were short-lived: Hitler regained permission to make speeches by the late 1920s. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, the resulting devastation and desperation set the stage for the Nazis’ comeback.

This time, Hitler had learned from his failures.

“Hitler’s lesson from the failed putsch was that he needed to pursue revolution through ‘the politics of legality’ rather than storm Munich City Hall,” wrote historian Christopher R. Browning for the Atlantic in 2022. “The Nazis would use the electoral process of democracy to destroy democracy.”

By 1930, following a successful propaganda campaign concentrated on the government’s inability to improve economic conditions, the Nazis were the second-largest party in Germany. In 1932, Hitler ran for the presidency. While he lost the election, the campaign bolstered his reputation among the German public.

Due to the Nazis’ growing influence, German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler his chancellor in 1933. In this position, Hitler began a surgical manipulation of the German political system, using the law to do away with a number of freedoms—speech, press, due process—and shore up his own powers.

The following year, Hindenburg died. Hitler, who had played his cards right, declared himself the führer. Nurtured under the guise of legality, Nazi Germany was born.