This California Museum Is Home to Hundreds of Nature’s Scents

Perfumer Mandy Aftel’s spellbinding collection of rare essences and artifacts is on display at the Aftel Archive of Curious Scents in Berkeley

“Scents are one of the most subtle and delicate charms of life,” writes American perfumer Mandy Aftel in her new book, The Museum of Scent: Exploring the Curious and Wondrous World of Fragrance. “They awaken sensibility, stir the mind, stimulate the imagination and revive memory.”

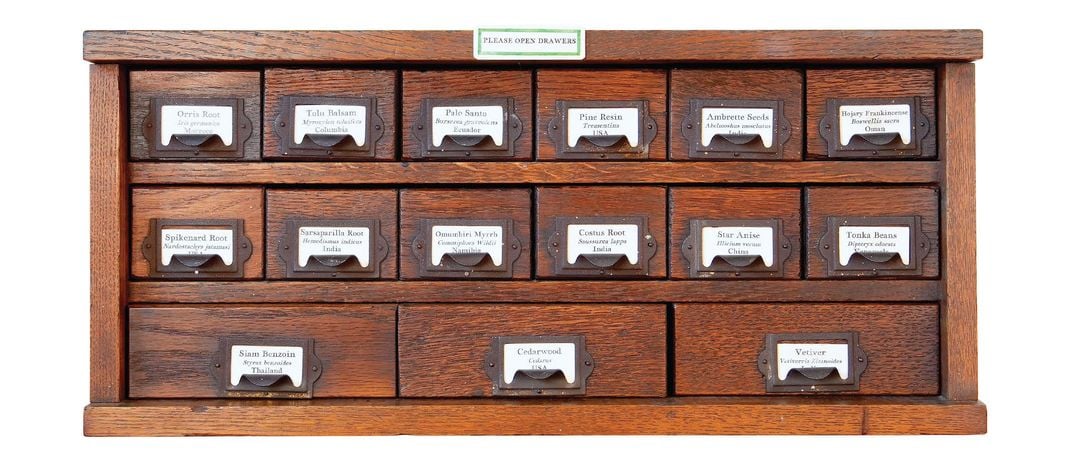

It’s true: The smell of gingerbread can take you right back to wandering that holiday market outside of London years earlier, and lavender can conjure up thoughts of a once-lingering summer day in France. In fact, just leafing through Aftel’s stunning compilation of olfactory magic is like being gifted a book of secrets, with chapters like “Botanical Treasure Boxes,” devoted to ways of displaying botanical raw materials such as the vanilla-smelling benzoin sap and calamus root, and “Ambergris,” all about the rich, musky marine scent that Aftel describes as “almost unearthly.” It’s filled with a bevy of perfume knowledge that’s been meticulously collected over time. But Aftel’s world isn’t limited to the pages. The author has a standalone cabinet of curiosities that you can actually visit in her own Berkeley, California, backyard.

Tucked away on a residential street within Berkeley’s Gourmet Ghetto neighborhood (the home of Alice Waters’ famed restaurant Chez Panisse), a true room of wonder awaits. The Aftel Archive of Curious Scents opened in 2017 and has been drawing crowds since, from commercial perfumers with a nose for aromas to gardeners, cooks and others who’ve never even heard of styrax (a sweet floral scent that oozes out of tree trunks) or boronia (a delicate and expensive floral), but who almost always leave intrigued. Some come from as far away as Europe and Asia; others are inquisitive neighbors from just up the street.

Splitting exhibitions between the stand-alone structure and an outdoor annex overlooking Aftel’s rose garden, the archive is a sort-of “please touch” (and smell) museum, one with a spellbinding collection of rare artifacts from around the globe. Along one wall, a taxidermy civet―a long-bodied and short-limbed cat-like creature—is paired with information detailing the animal’s role in ancient perfumery, including the forced secretion of its perineal glands, which produce a “fecal-floral” scent. Near another wall, a mid-19th-century tiger oak cabinet, with curved glass doors and glass sides, displays objects ranging from a 17th-century artisan pomander―a type of open metalwork ball made to hold aromatic spices and herbs as a protection against infection―to Victorian perfume buttons, each one fashioned with an interior cloth meant to absorb and hold fragrances. It’s a collection that’s been 30 or so years in the making, with Aftel acquiring centuries-old tomes brimming with perfume recipes from antique book fairs and rare book dealers, buying stashes of oils from long-time perfumers, purchasing some items online from reputable sellers and even receiving donations.

“I wanted the experience of entering the archive to be beautiful,” Aftel tells me over the phone. “For people to be in that present moment where they just go, ‘Oh, my god.’”

Aftel started making natural (she uses nothing synthetic) perfumes a few decades ago, lured as much by the quest of assembling essences from the planet’s far corners as by the project of creating her own scents, which she hand-blends and bottles in small batches. The perfumer looks for rare essences, such as gardenia and honeysuckle, that you can’t find elsewhere, and has such a reputation for purchasing these elusive oils that people often come to her with them. “I actually learned about the gardenia,” says Aftel, “from a student of mine who was traveling in Tahiti and ran into a person who grew and extracted the essence. She introduced me to him, and I bought out every last drop that he had.” Aftel sells her fragrances through her website, shipping perfumes to places like England, Japan and everywhere in between almost daily. “When buying from me, I always suggest that people should start with samples, which we have for every fragrance I make,” she says. “This way they can see how it interacts with their body chemistry.”

But while Aftel had firmly established herself in the olfactory world with her 2001 book Essence and Alchemy: A Natural History of Perfume, seminal in many perfumers’ training, it wasn’t until the mid-2010s that the idea of opening her collection to the public came about. “About 60 percent of what’s in the museum had been in my studio,” says Aftel. “Whenever I had visitors, I would always take things out and show them around. Everyone always seemed to be so surprised at what they saw and kind of loved it, which thrilled me. But then they’d leave, and I’d have all this stuff that I had to put away.” So Aftel started considering another way to share her stock with others. Inspired by tiny, small-town museums of California Gold Country—ones featuring authentic treasures like real gold nuggets and 49er mining equipment—the perfumer decided to give a similar venture a go.

Without any professional design training of her own, Aftel put the archive together through trial and error. “It’s a study in beauty,” she says. The space itself is outfitted with hardwood floors and natural woods, Art Deco-style light fixtures, and even a comfy window seat for paging through Aftel’s incredible selection of antique books, with titles like A History of the Use of Incense and Spices and How to Know Them. It looks quick to explore, but that’s before realizing that each bottled essence (“essence” is an umbrella term Aftel uses for the museum’s many scents) contains a world all its own.

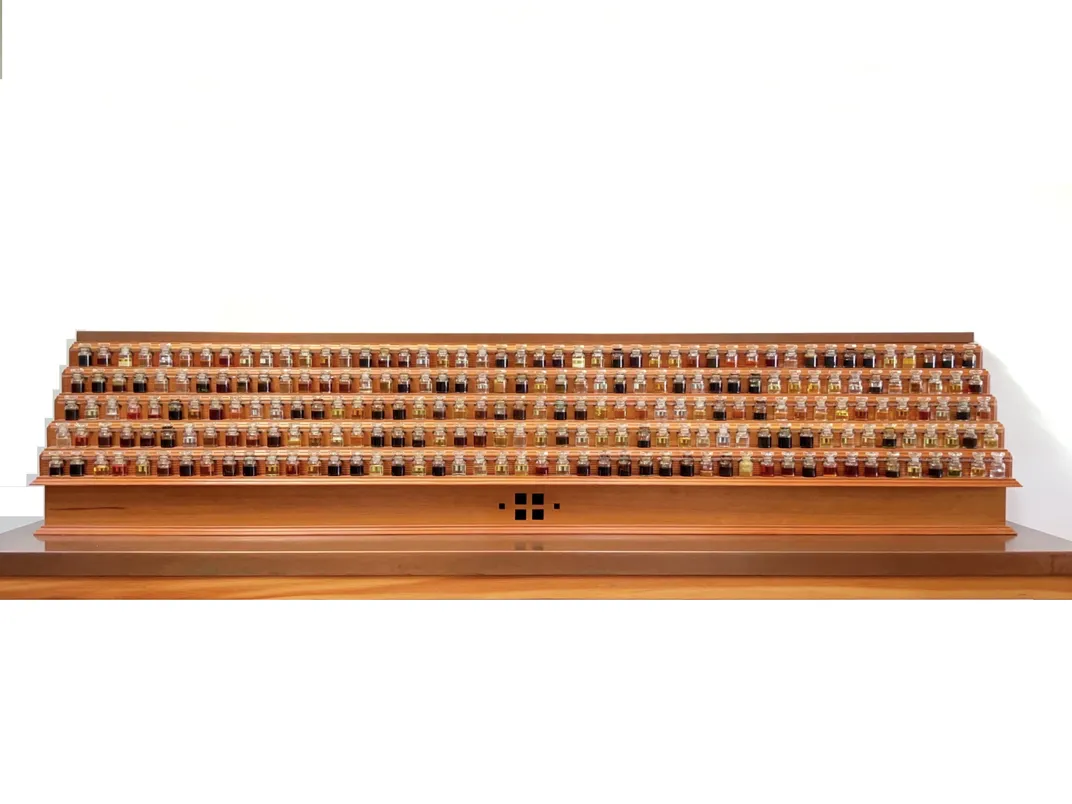

A couple hundred of these essences make up the archive’s “perfume organ,” a five-row display that’s similar in style to the keyboard instrument it’s named for. There are top notes, middle notes and base notes (the different layers of a larger scent), each of them arranged in alphabetical order. Some are familiar aromas like grapefruit and chamomile, while others are more obscure. Galangal, for instance, is a complex and tangy spice that smells like a mixture of cardamom, ginger and saffron; ancient Egyptians often burned it to disinfect the air.

“There are a few things I’d say that make the space really special,” says Antonia Kohl, co-founder of Ministry of Scent, a San Francisco storefront devoted to selling indie perfumes and niche fragrances. While the perfume organ is one of them, she says, the true gift is Mandy herself. “She is such a consummate researcher, teacher and collector of rare olfactory treasures. When you go there and get to meet her … it’s incredible. You almost never get a chance to meet someone with that depth of knowledge who’s also willing to share what they have.”

Perfumer Mauricio Garcia, founder of Herbcraft Perfumery, agrees. “Mandy is a master of curation,” says Garcia. “I have heard her tell stories about the different essences that she’s sourced, where she sourced them from and how much time she’s taken to find, say, the perfect bergamot and the perfect lavender, and always paying attention to all the different nuances that make the materials that she offers jewels.”

The Museum of Scent: Exploring the Curious and Wondrous World of Fragrance

Breathe in the natural and cultural history of scent with this richly illustrated book inspired by the Aftel Archive of Curious Scents.

To keep the traffic flow moving through the archive, tickets allow visitors (nearly half of whom, says Aftel, are repeat guests) approximately one hour to peruse both its indoor and outdoor space, neither of which has any specific order. You might find yourself marveling at hand-tinted postcards and engravings (some of which date back over 400 years) one minute, and handling raw ingredients such as bushman’s candle—a fallen desert bark that’s gathered by Namibia’s Himba tribespeople and then burned for its musky and spicy smoke—the next. Aftel herself is a constant fixture in the museum—along with her son, Devon, and sometimes her husband, Foster—who are all on hand to answer any questions.

Every visitor also gets a take-home kit that includes four letterpress scent strips dipped in one of the archive’s natural essences (there’s material on hand to help you select your favorites), an AromaCone scent magnifier to use outside in the Garden Annex and a personal glove for handling the antique books. The latter has been an especially big hit, says Aftel. “Before I started offering them, no one would touch the books,” she says. “I feel like the gloves just gave people permission to no longer be afraid.”

Although masks are still required indoors, in the museum’s outdoor Garden Annex, visitors really get to engage their olfactory sense. There’s an opportunity to “deconstruct” one of Aftel’s own perfumes, and another to smell the differences between natural and synthetic aromas. Another display showcases the differences between ancient and modern versions of the same bottled scent. “So you can smell the aging process,” says Aftel, which in many ways might reflect that of a fine wine. The Garden Annex is also where you’ll find the archive’s historical animal essences like hyraceum, the petrified excrement of small hyrax mammals (the complex and pungent fragrance is often used to balance out a sweeter scent), as well as a rotating temporary exhibit. The one currently on display highlights wood essences such as cypress, fir and oud.

But while Berkeley isn’t around the corner for everyone, Aftel’s Museum of Scent is a much easier reach. The 264-page hardcover provides a lot more background on many of the museum’s exhibits. The book, for example, groups a sampling of the pipe organ’s individual essences into chapters of simple fragrance families—flowers, citruses, woods, gourmand, leaves and grasses, herbs, resins, isolates, and spices—and then accompanies each of them with a photocopied and hand-painted (by Aftel herself) rendering of its own plant source. The latter is a way for readers to connect with the raw materials that the essences come from. Aftel’s text then details the distinct character and personality of each of these essences, from juniper berry to lemon myrtle. So while the museum is more multi-sensory, the book offers readers a chance to linger with the pieces that most speak to each reader.

It’s almost like getting Aftel and her expertise all to yourself.

One-hour entry to the Aftel Archive of Curious Scents is $25 per adult and $15 for children 17 and under. Open Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., only.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.