Rony Cohen doesn’t remember any particular moment when she first became aware of the number tattooed on her grandmother’s arm. It was just always there.

Cohen, a 41-year-old living in Israel, felt as if she had experienced the Holocaust herself, in a different cycle of her own life. It featured in her dreams. It permeated family life, as did the self-imposed interdiction on talking about the past and the absence of relatives. The legacy of starvation was never far from the surface. Food was used to soothe. There was no waste. Her grandfather finished every crumb from every plate.

The influence the Holocaust has had through the generations runs deep, and how each descendant of survivors remembers the past and its legacy varies hugely. Cohen is one of a number of the children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, more specifically survivors of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp, who have chosen to replicate their family member’s tattoo on their own body.

Auschwitz, in Nazi-occupied Poland, was the only camp where numbers were tattooed on those prisoners not selected for immediate death. Over the course of Auschwitz’s existence, more than 400,000 prisoners were assigned serial numbers. Cohen draws meaning from her tattoo in that it signifies her grandmother’s history and her own identity as a descendant of Holocaust survivors. To her mind, replicating this number was a means of taking both her grandmother as a person and her grandmother’s legacy forward. As a gesture and an indelible mark she carries with her, Cohen says, “The number is my grandma. It’s my past, my roots, my story. It’s who I am.”

A potent gesture

My research delves into the stories of those descendants who, like Cohen, have chosen to replicate a parent’s or grandparent’s serial number tattoo on their own body. Of the 16 people I have spoken with, 13 are from Israel and 3 from the United States.

As the number of remaining survivors of the Nazi concentration camps grows ever smaller and the Holocaust passes out of living memory, replicating an Auschwitz tattoo becomes to these descendants an ever more potent gesture about embodied memorialization and, crucially, familial ties and love.

The people I have spoken with have relayed complex and varied decision-making processes behind this action. The tattoos’ designs aside, tattooing in general is considered taboo among many Jews for religious and cultural reasons. Some waited until their survivor parent or grandparent had died. Others got the tattoo without seeking approval. Still others discussed the procedure with their relative beforehand.

The replica tattoos vary in terms of font, color and placement. Some individuals have chosen to replicate exactly what the original looked like and where it was placed. Others have chosen to alter the designs in detail and color, or to place it on a different part of their body. Each decision crafts its own independent meaning.

Orly Weintraub Gilad, a 45-year-old Israeli, chose to have her maternal grandfather’s number tattooed on her arm. But the tattoo was also for her maternal grandmother, who had been imprisoned at Auschwitz but was never tattooed because she was not expected to survive.

Weintraub Gilad remains very close to her grandmother, who is now 95 years old. She says the tattoo gives her the chance to tell her grandmother’s stories and talk about the Holocaust with others. As Weintraub Gilad explains, “It starts the conversation, and that’s the purpose.”

The tattoo itself features her grandfather’s number in a nest of leafy green vines, a nod to her love of nature. Letters emerge from different vines—the initials of Weintraub Gilad’s husband and her children.

Even though her grandfather’s number was on his left arm, Weintraub Gilad placed her own tattoo on her right arm, because she wanted “to do it the same but different.” One reason for choosing the right arm was because she did not want to see the number “on the side of the heart.”

After their release, the men started their journey back home, but to pass through the British-occupied military area without being detained, identification was required. Neither man had any, so they tattooed what looked like Auschwitz numbers on their left arms. When Ron shared what he had learned with his family, they took pride in Reisz’s “creativity and thinking out of the box.”

Ron first thought about getting his father’s number tattooed on his own body when he was around 50 years old, at the turn of the millennium, when Reisz was still alive. Reisz was strongly opposed to the idea but eventually agreed.

Having the number on his own body, Ron says, allowed him to reflect on what it is to live “like a numbered person.” As survivors die out, he dwells on the thought that soon there will be no numbered people. This, to his mind, makes the number an important thing to keep—a tool for keeping the memory alive.

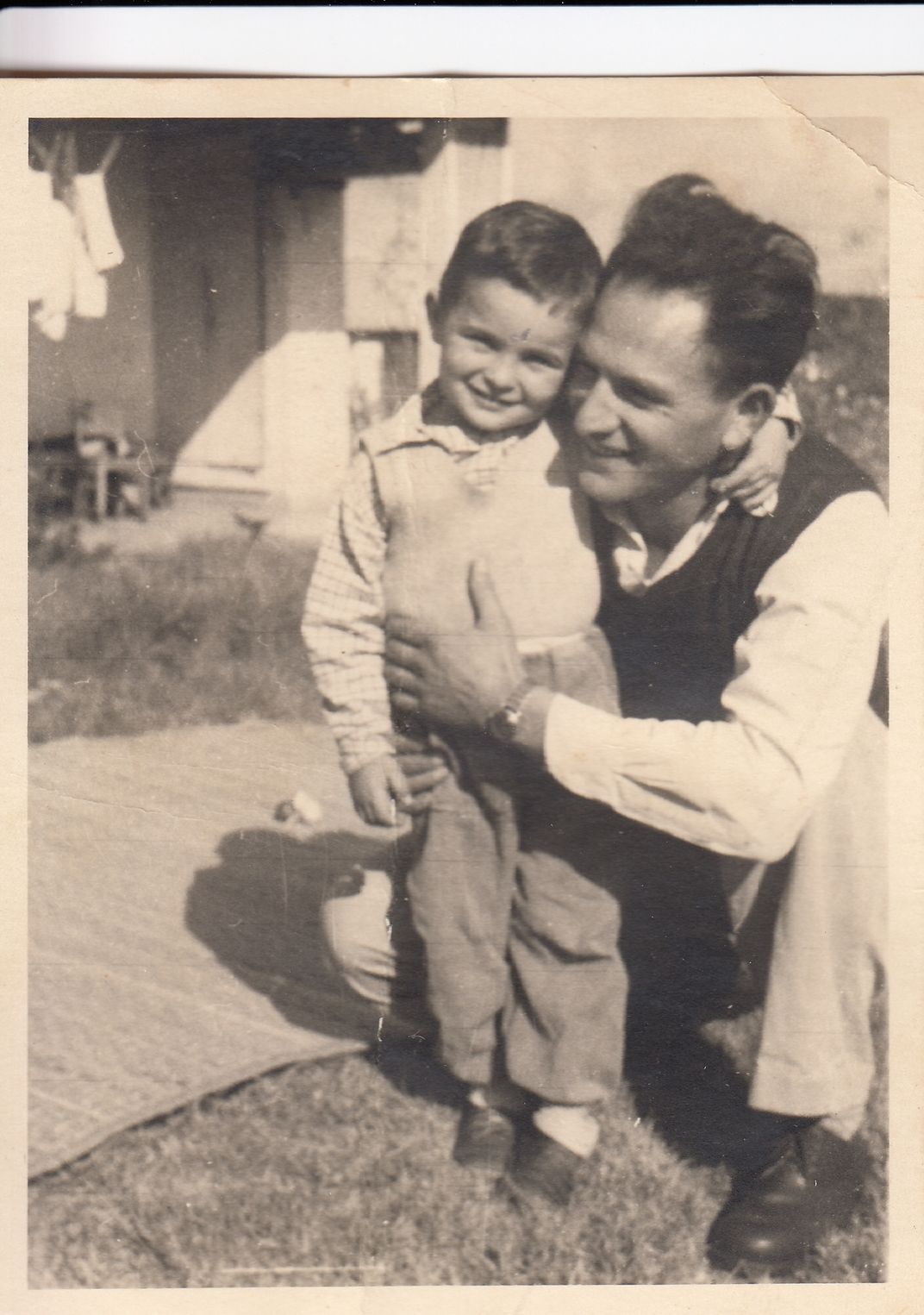

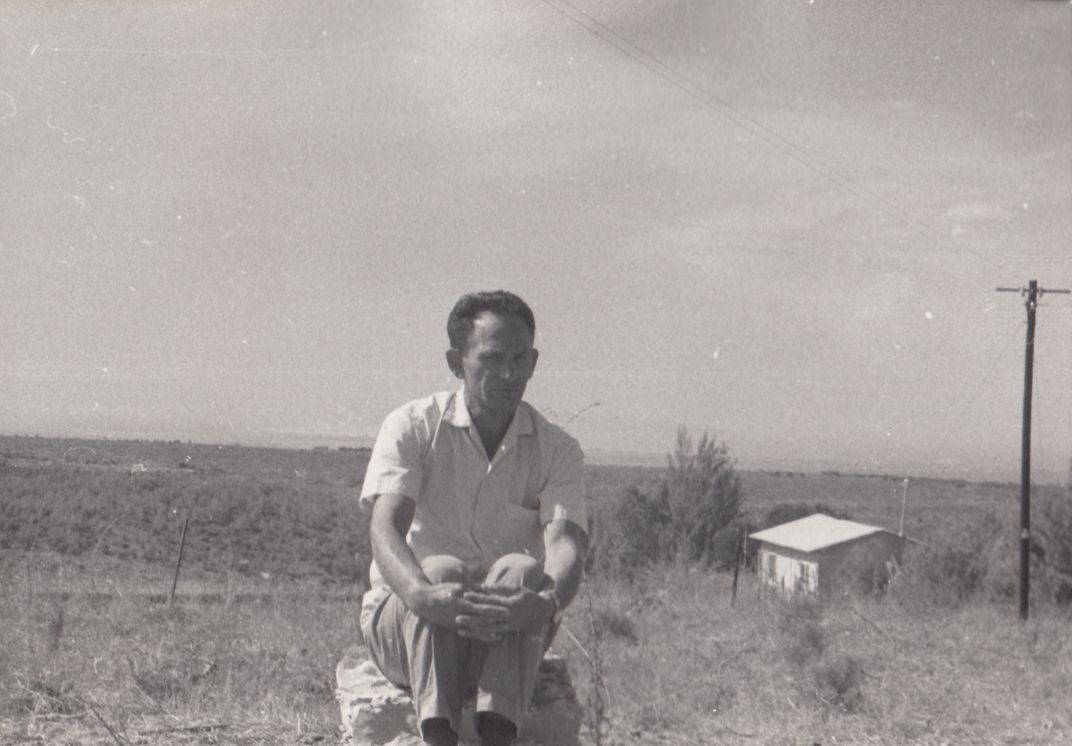

I also spoke with Yair Ron, a 72-year-old who grew up in Israel on a kibbutz founded by Holocaust survivors. No one in his community had grandparents or spoke about their suffering. Ron’s father, Jakub Reisz, who everyone knew as Yakshi, said nothing about the Holocaust and, like many children of survivors, Ron and his sister knew not to ask.

Ron first noticed his father’s tattoo as a child. Just as it was normal not to talk about things—about families, generations, loss—it was also normal to him and his peers that adults had numbers inscribed on their bodies. Until he started venturing out into the local town as a teenager, he hadn’t really met adults who didn’t have numbers.

It was only after his father’s death that Ron started to piece together the unconventional story of how his father got his tattoo. Coming across a letter and diary written by his father’s friend, Ron discovered that both men had been deported from Slovakia, imprisoned in Auschwitz and then transported to Nazi-run work camps, from where they were eventually liberated. For unknown reasons, they were not tattooed at Auschwitz.

Tattooing in Auschwitz

Serial number tattoos with symbols, shapes or letters were first introduced for prisoners in the Auschwitz concentration camp complex in October 1941. The only people exempted from tattooing were ethnic German and Austrian civilians, police prisoners, and Polish prisoners deported from Warsaw during the 1944 uprising—plus Jewish prisoners held for a short time while waiting to be moved to other camps.

Prior to tattoos, identification numbers were sewn onto the prison uniforms. Soviet prisoners of war were the first group to be tattooed, after larger numbers started to die and the other prisoners took the deceased’s clothing, making it impossible to keep accurate records.

Initially, the tattoos were placed on the left side of each prisoner’s chest. The individuals who performed the tattooing used a metal stamp fitted with needles that wrote out different numbers. This technique enabled guards and prisoners to imprint a serial number onto a prisoner’s body with a single action. They then rubbed ink into the bleeding holes.

By spring 1942, all incoming Jewish prisoners selected for forced labor, rather than immediate death, were tattooed. In place of the metal plate, the tattooists now used a single needle to puncture the number into the prisoner’s skin by hand, then rubbed in the ink.

The numbers were tattooed on the prisoners’ left forearms. Shapes and letters were sometimes also used to differentiate between groups of prisoners. Some Jewish prisoners had a triangle tattooed under their number. Roma and Sinti prisoners had the letter Z appended to their number, the first letter of the pejorative German word Zigeuner, which was used at the time for these communities.

With Hungarian Jews arriving in increasing numbers, new sequences of digits were introduced in May 1944. These began with the number 1 and were prefaced first by the letter A, then, when more were needed, B.

In her autobiography, Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered, German studies scholar and Holocaust survivor Ruth Klüger described the experience of getting forcibly tattooed in Auschwitz:

[After selection], we got our ID numbers tattooed on our left arms. A few female prisoners had been installed outside the building at a table with the necessary equipment and we stood in line, waiting our turn. The women knew their job, and they were fast. At first it looked as if the black ink would easily wash off, and indeed, water took most of it away, but then the fine points of my number remained: A-3537.

Klüger spoke about “the victims’ skin” saving the Nazis from having to produce “dog tags”—a statement that underlines just how dehumanizing this Nazi practice of tattooing numbers on inmates was. As the Italian writer and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi put it in The Drowned and the Saved:

Its symbolic meaning was clear to everyone: This is an indelible mark, you will never leave here; this is the mark with which slaves are branded and cattle sent to slaughter, and that is what you have become. You no longer have a name; this is your new name.

An embodied public memorial

For Cohen, a tattoo’s visibility is important. “I was proud to take my grandmother with me,” she says. Her grandmother’s stolen childhood, the years she spent missing her parents—those moments are in this number. “Whenever someone sees [my tattoo], they know this is Auschwitz. I want it to be noticed and understandable. No one should doubt what it is.”

Cohen’s grandmother and great-uncle were of the cohort of siblings that have become known as “Mengele twins,” after Nazi physician Josef Mengele, whose interest in racial genetics led him to conduct barbaric experiments in the camps. He first experimented on Roma and Sinti twins in what was known as the “Gypsy camp” in Auschwitz-Birkenau, then on Jewish prisoners he picked from the Theresienstadt camp-ghetto.

Starting in May 1944, subjects for Mengele’s experiments were also picked from the unloading ramps at Auschwitz. Cohen recalls a story her grandmother told her, about how she arrived at the camp with her 8-year-old twin brother, her mother and aunts, and all the other children of the family: “They saw the smoke from the crematorium. The family was walking, and someone was saying, ‘Twins, twins, twins, where’s twins?’”

Instead of hiding them, the narrative goes, the mother said to the aunts, “Let’s give them the twins.” The aunts thought she was crazy for suggesting that, but the mother thought she was saving her children. “I’m going to save your life now,” she told them. “Give mommy a hug, and you’re leaving now.” This was the last moment Cohen’s grandmother could remember being with her mother.

Twins were sometimes given additional food that helped keep them alive. Firsthand accounts describe how Mengele gave his victims chocolate before carrying out the most horrific experiments. He sewed twins’ veins together, injected chemicals into testicles and spines, and inserted large needles into skulls.

In the 1994 book Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, historian Helena Kubica recounted testimony given by Moshe Ofer, a man who was imprisoned as a child with his twin brother, during a tribunal that tried Mengele in absentia in 1985.

Mengele killed Ofer’s brother with his experiments.

Ofer described how, after Mengele’s sessions, the physician would bring gifts. The horror of that never left him. “Even today,” he said, “I can see him entering through the door and am paralyzed with fear.”

Cohen’s grandmother similarly recalled Mengele bringing food for the twins. It saved them physically, she said, but the psychological damage was immeasurable. As Cohen puts it:

My grandmother, since the Holocaust, has a sleeping disorder. In her dreams, her parents come, and all the horror comes. She always tells me, “I can’t forgive myself that I remember Mengele’s face, but I can’t remember my parents’ faces.”

Her brother—Cohen’s great-uncle—had his tattoo removed after saving enough money. Her grandmother, by contrast, still bears it on her left arm.

As a child, Cohen would ask questions about the Holocaust. Sometimes her grandmother would make out that it was nothing. Sometimes she’d say she would tell her when she was older. Cohen describes herself as stubborn; she just kept asking.

When she was 12 or 13, for a school project on roots, she decided to film a video on her family’s history. Cohen interviewed both of her maternal grandparents. Her grandfather she describes as “tough,” with “all the characteristics of a typical survivor.” He was keen that Cohen pass on all the information to her mother because, he said, “Your mom never asked.”

Cohen shared everything with her mother and her uncle—and it finally removed the elephant from the room. It made talking about the Holocaust possible for them.

At 17, like so many Israelis, Cohen went on a high-school visit to the camps and the ghettos. Before leaving, she went to see her grandfather. He told her that going to Auschwitz would change everything:

When you stand there in those walls and you smell the death smell and you see the gas chamber, you will come back to Israel and you will tell me, “I can’t understand.”

“I can’t understand,” Cohen now says. “My grandfather was so right.”

How Holocaust memorialization has changed

In the aftermath of World War II, public commemorations of the Holocaust celebrated resistance and uprisings. The victims and survivors, by contrast, were portrayed as weak. The stigma felt by some survivors followed them throughout their lives, even when public perception started to shift. Some, like Cohen’s great-uncle, had their number removed. Others covered it up with long sleeves.

As French historian Annette Wieviorka explains in The Era of the Witness, attitudes began to change in the early 1960s, partly due to the testimonies heard during the trial of Adolf Eichmann at that time. Reporting on the trial from Jerusalem for the New Yorker, the historian and philosopher Hannah Arendt gave survivor voices a global platform. The trauma that emerged from Eichmann’s trial reframed survival in itself as something heroic.

Then, in 1967, Israel responded to threats from Egypt and other neighboring states with an offensive that allowed it to expand into and occupy the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Further afield, the conflict—known as the Six-Day War—built an affinity between Jewish communities in the U.S. and Israel. Many American Jews began to both embrace their European roots and support Zionism.

Wieviorka’s book explores the third (and ongoing) phase of Holocaust memorialization: the “era of the witness,” which emerged in the 1970s. People started collating survivor testimonies, photographs and documentation. Through visits to the camps and ghettos, families began to tell their stories. For some descendants of survivors, the visit to Poland also set off the process of replicating the Auschwitz number on their own body.

I also spoke to Zeev Forkosh. Now 38 years old, he has multiple tattoos—but the idea for his first one came after visiting Auschwitz.

The new information Forkosh learned during that trip, about what his grandmother had experienced there, sparked such powerful emotions that he decided to get a Holocaust memorial tattoo. He describes the large Star of David he wears on his back as entwined with “bones, flesh and a lot of clothes, like the Holocaust survivors.”

Next, Forkosh decided to replicate his grandmother’s number on his arm, explaining:

I will never forget this trip, so it’s on my back now. But after a few years, I wanted to be more specific about my grandmother. I told the tattoo artist that this was for [her]. I’m a third generation of a Holocaust survivor. I think it’s the most beautiful tattoo ever.

Talking about this number in terms of beauty underscores how reproducing the tattoo gives it new meaning. It is a gesture that, for Forkosh, turns the visual symbol of a genocide into a symbol of love and legacy, of commemoration and pride.

This marks a radical shift from survivors’ own relationships with the number. They had no choice in the matter; the tattoo was forcibly placed on their bodies. For descendants who have suggested replicating the tattoo to their parent or grandparent, the answer was initially a categorical “no.”

Ron discussed the idea with his father, who did not approve of it. “Why?” he asked. “You don’t need to, it’s not good. Let’s forget everything.”

Ron kept trying: “It took a few years for us to talk about it. And then he agreed for me to do it.”

Ron gave the tattoo artist a photo of his father’s number, seeking to replicate it as closely as possible. He wanted people to ask about it, to keep the Holocaust in living memory.

In Ron’s mind, his actions represent continuity. They ensure there are still people “walking with the number.” He says he wanted to experience what his father had experienced when his humanity was replaced with a number.

Similarly, Rony Cohen says that deciding to replicate her grandmother’s number was so “she could walk with me for good—it’s a statement for me.” Cohen wanted her tattoo in the same place as the original, so that everyone understood its meaning. She sees her body as becoming a conduit for her grandmother, a means of keeping her legacy and life with her at all times.

In contrast to Ron, though, Cohen did not broach the subject with her grandmother. She just went ahead and got the tattoo, then wore long sleeves at family gatherings—much as some survivors had in previous decades. But for her, covering the tattoo wasn’t because of the same stigma. Rather, she worried about the reactions it might produce.

Eventually, Cohen decided to show the number to her grandmother. At first, her grandmother asked why Cohen had done it. Then she asked if it hurt. “I don’t want you to do something that hurts,” she said.

“No, it didn’t,” Cohen replied.

To which her grandmother asked, “Why?”

Cohen is very clear that getting her tattoo was a personal act, a decision relating to her own history, not to a larger historical one. “I’m not a monument,” she says. “I don’t carry the Jewish nation on my back.”

When the Holocaust passes out of living memory

Despite the proliferation of Holocaust-related art and culture, despite the books laying out the facts, research shows many people are ignorant of what happened. In 2021, a global survey found large gaps in people’s knowledge.

In the United Kingdom, 52 percent of respondents could not specify that six million Jewish people had been murdered. This number rose to 56 percent in Austria and 57 percent in France. Of the adults surveyed in the U.S. and Canada, 45 percent and 49 percent, respectively, were unable to name a concentration camp or a ghetto. Among millennials and members of Generation Z in the U.S., only 48 percent could name a concentration camp or ghetto.

With the 79th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz arriving on January 27, very few survivors are left to give a firsthand account of what was done to them. The Holocaust is passing out of living memory.

For those whose family history is tied up with the Holocaust, memorializing it is both public and private. To the individuals I’ve interviewed, replicating the Auschwitz number is a form of memorial practice that speaks, viscerally, to their own family history, but also to the imperative to never forget.

David Rubin, a 38-year-old from Israel who currently lives in the United Kingdom, bears his grandmother’s number on his arm, the number depicted as if written on a piece of wood alongside a Star of David, a thorny vine of lilac-colored flowers entwined around it.

Four of the flowers are open, representing his grandmother and her surviving sisters. To the left lie two closed flowers, for her two sisters who were killed in the Holocaust. A lone flower completes the floral framing at the bottom, in memory of her brother, also killed.

To Rubin’s mind, his generation is probably the last to speak about the Holocaust. Getting the tattoo was a means of ensuring that the fourth generation—his children, his grandmother’s great-grandchildren—will know what happened. “I wanted a story, instead of just a number,” he says. The barbed wire has become the thorny vine in flower. “It’s taking the bad thing and [re]creating it as a good thing.”

As the writer Eva Hoffman notes, even though families, including her own, reckon with their traumatic past in silence, the “language of the body” still breaches those silences. It keeps the unspoken past ever present.

While descendants of Holocaust survivors did not experience the trauma directly, the intergenerational trauma is long-lasting. Cohen was not the only grandchild of a survivor who told me they dream or have nightmares about the Holocaust.

In doing these interviews, I have found that replicating the Auschwitz tattoo is an expression of the love felt toward the survivor relative and a way of keeping the memory of the Holocaust alive, as well as an act of reclaiming a painful family history. For some, it is also about connections to a collective identity.

In this way, it is about the future, too. When there are no more survivors to share their stories, these descendants who bear on their living bodies the numbers once forcibly tattooed on their relatives will stand as a living reminder of where racism and hatred can lead.

This article is published in partnership with the Conversation, the news and features website written entirely by academics. Read the Conversation’s version.

Alice Bloch is a sociologist at the University of Manchester in England. She is writing a book about intergenerational memory practices among the descendants of Holocaust survivors who have replicated their ancestors’ Auschwitz concentration camp numbers on their own bodies. This work was supported by a grant from the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust Small Research, in partnership with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.